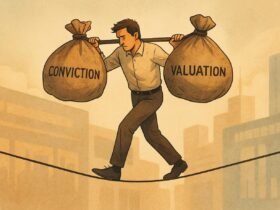

A real investor’s reflection on Trent — and the fine line between conviction and concentration.

Image created in-house by Shikshan Nivesh using AI tools.

I’ve seen investors lose money in terrible businesses.

But I’ve seen more people lose far more money in great businesses… bought at the wrong price.

This is the story of one of them.

The Friend Who Kept Buying

He first bought Trent at ₹2000.

Then again at ₹3000.

Then ₹5000.

Then ₹7000.

By the time it hit ₹8200, Trent made up 45% of his entire equity portfolio.

He wasn’t reckless. He wasn’t new.

In fact, he was one of the sharpest friends I knew in the market.

But he made the most common mistake smart investors make:

He fell in love with a story.

In his case, the Tata Group story.

He’d made 10x on Tata Motors during the COVID rebound.

From that day on, he believed everything the Tata Group touched would eventually turn to gold.

And to him, Trent wasn’t just a retail company — it was a lifestyle.

Zudio stores were everywhere.

Margins were rising.

Earnings looked explosive.

The momentum was magical.

And who doesn’t love a fashion format that’s eating the Indian middle class for breakfast?

He thought he was riding the next Titan.

I told him to be careful.

Not because the business wasn’t good — it was.

But because I felt the numbers weren’t keeping up with the price.

I still remember the message I sent him in July 2024 — Trent was trading at ₹5,799 then.

The P/E was 228.

The EV/EBITDA was 94.

The price was up 3x in just 14 months.

“I feel the risk/reward here is totally skewed,” I told him.

“This might be a multi-year top.”

He disagreed.

And to be fair… he was right for a while.

Trent kept going.

And I stayed out.

But over the next few quarters, something started to change — not in the business, but in the numbers behind the business.

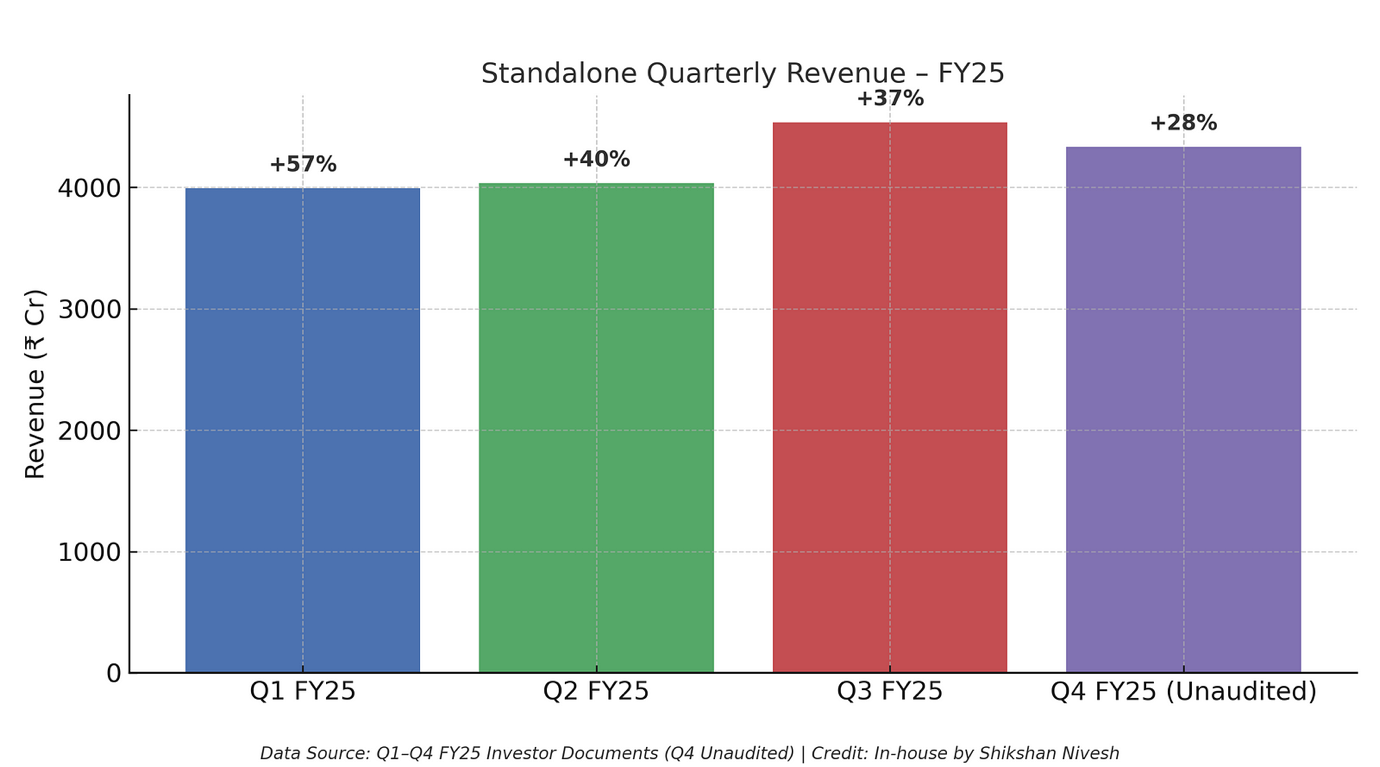

What you’ll notice here is subtle — but critical.

Yes, the revenue kept growing.

But the pace of growth kept slowing — quarter after quarter.

From +57% in Q1 to +28% in Q4. That’s a big deceleration in less than a year.

For a business priced like it’s on a rocket ship, even a soft landing can shake the story.

And that’s exactly what started to happen next.

The Beauty of a Good Business — And the Trap

Let’s be clear about something: Trent is a beautiful business.

Zudio is one of the most exciting consumer stories in India today.

It’s fast, it’s affordable, and it’s everywhere.

Westside has evolved from a quiet department store to a formidable middle-class fashion engine.

Margins have improved.

The store experience is consistent.

Execution is tight.

And they’re doing it without needing debt.

So yes — the business quality isn’t in question.

The trap is when we confuse business quality with investment quality.

Here’s what most people missed while cheering the growth:

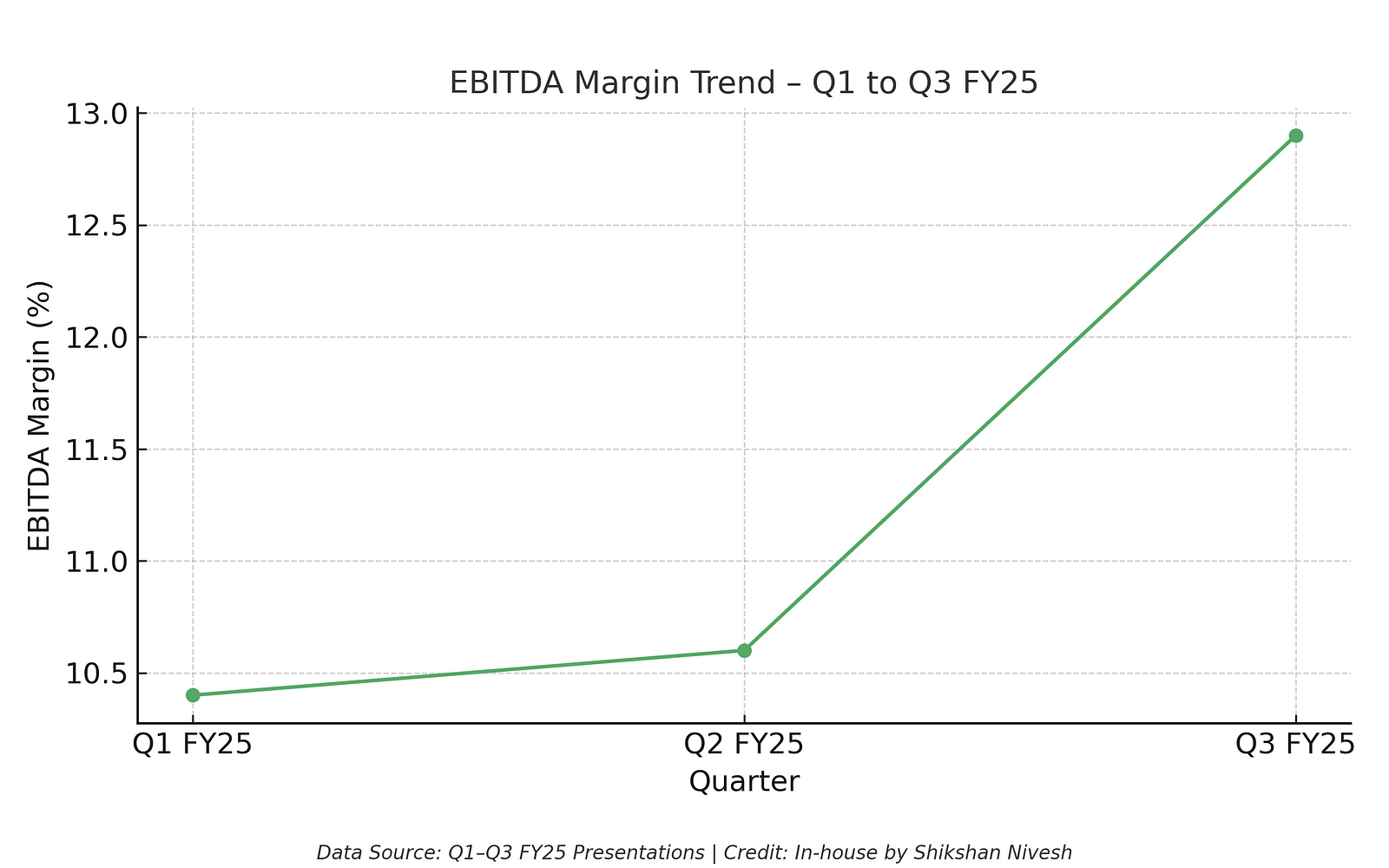

At a glance, that chart looks great. Margins are rising — and that’s true.

But here’s what it hides :

🔍 While revenue growth was slowing, margins were rising

🔍 Which means… the valuation multiple was rising on a slowing top-line

This is where the story started drifting away from the numbers.

Margins were the last thing holding the “valuation doesn’t matter” crowd together.

And even that had a ceiling.

Because even the best operators can only extract so much per square foot — especially when growth becomes aggressive.

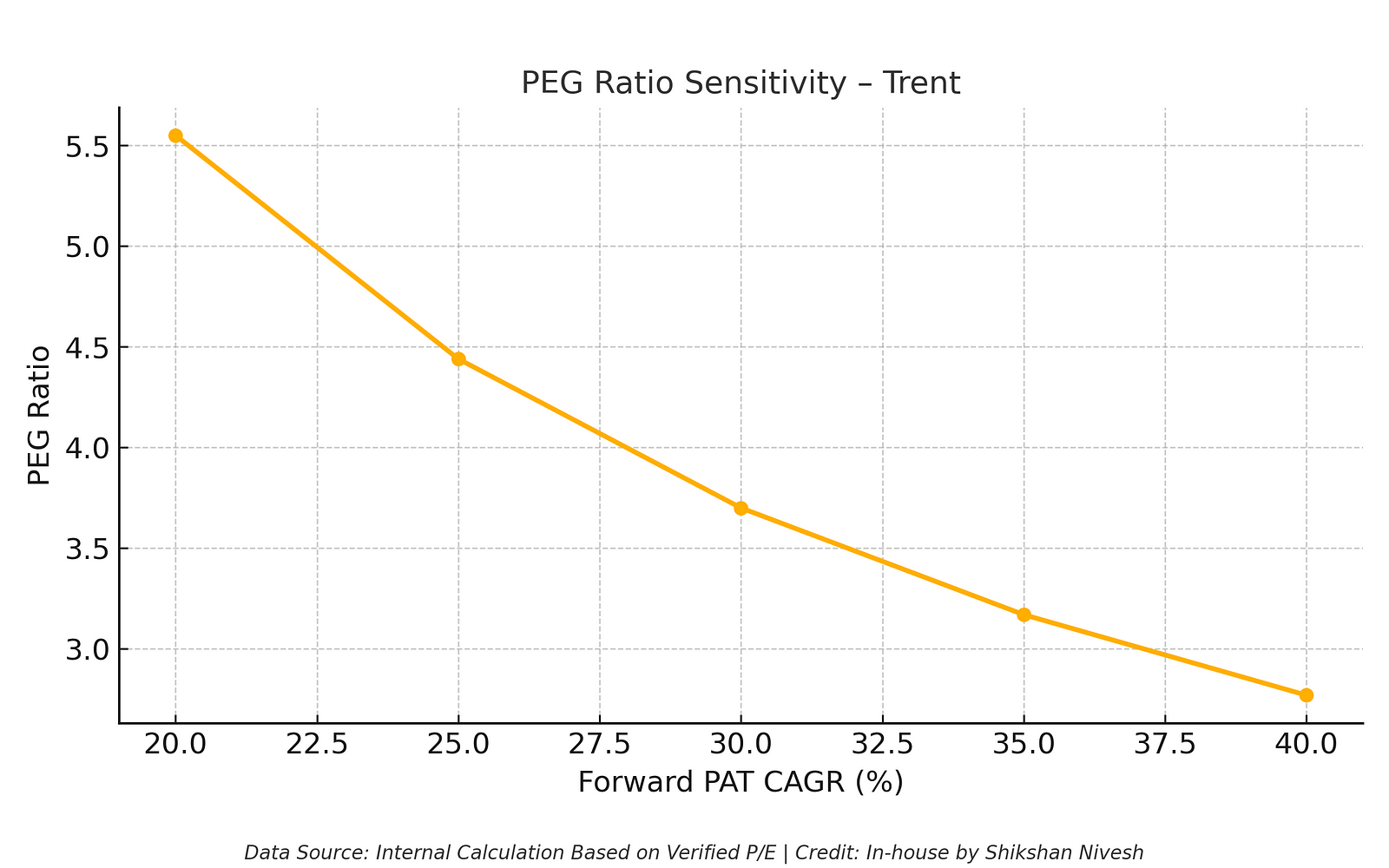

The PEG Disconnect

Here’s a number that rarely lies: the PEG ratio.

Most people obsess over P/E — but PEG is where you actually understand how much you’re paying for how much growth.

At its peak, Trent was trading at a P/E of 228.

Even after the recent correction, it’s still hovering around 111x earnings.

Now, that number might be fine… if you’re growing 50–60% year after year.

But what if you’re not?

Let’s look at what happens to Trent’s PEG ratio across different future growth scenarios:

Even if Trent grows PAT by 30% a year, its PEG is still close to 3.7.

That’s expensive. Very expensive.

Especially when the SSSG is tapering, margins are plateauing, and execution is reaching saturation.

PEG is not a perfect metric — but it’s a damn good warning light.

And in Trent’s case, that light was blinking bright red.

A PEG of 5.6 at 20% earnings growth?

That’s not aggressive pricing. That’s pricing in a fantasy.

What’s Still Going Right at Trent

Let’s not forget — this isn’t a teardown.

Trent is still executing well.

In fact, in some operational metrics, it’s doing better than ever.

One number I personally love tracking in retail is revenue per square foot.

Because it shows you how well the stores are performing, not just how many there are.

That’s a near 51% improvement over three years.

This tells you two things :

- Their store formats are becoming more efficient

- They’re extracting more throughput per sq. ft., even while scaling

This is rare. Most retailers lose productivity when they expand rapidly.

Trent didn’t — at least not yet.

But the problem is: the price was reflecting too much of that goodness, too soon.

But Here’s Where It Gets Complicated

So far, we’ve looked at Trent like it’s one smooth machine — and to some extent, it is.

But once you zoom in, things get a little more fragmented.

Let’s start with the JVs.

Zara continues to perform strongly — ₹2,769 Cr in FY24.

But Star Bazaar is still loss-making at ₹2,189 Cr.

Which means… when you look at the full business, you’re not looking at just Westside and Zudio anymore.

You’re looking at multiple vehicles, some moving forward fast, some dragging weight.

Then comes the more subtle concentration risk:

How much of Trent is just Westside and Zudio?

A portfolio that looks diversified is, in reality, heavily dependent on just two engines.

If Zudio stumbles or Westside slows down — the whole thesis takes a hit.

The Hidden Divergence

If there’s one thing that gets investors excited, it’s expansion.

More stores. More cities. More formats. More scale.

And Trent delivered exactly that.

In FY25 alone, they opened 244 new Zudio stores.

Let that sink in.

That’s nearly 5 new stores every week.

But here’s the thing no one wants to talk about:

What if your same-store sales start slowing…

…while your store count keeps rising?

Let me show you what that divergence looks like:

Zudio store count rose from 233 to 765.

But estimated SSSG (Same Store Sales Growth) dropped from 18% to 12%.

This is the classic scale vs saturation dilemma.

You’re expanding.

But if each store sells slightly less, your expansion is just masking a slowdown.

It’s like running faster… just to stay in place.

One Wild Story About Trent

Everyone talks about Zudio now.

But the truth is — Trent wasn’t always taken seriously.

In fact, Trent was once seen as the forgotten child of the Tata Group.

Back in the mid-2000s, Westside was a struggling format. The stores were patchy. Inventory was inconsistent. People compared it to Shoppers Stop — but mostly to explain why they wouldn’t shop there.

Then something changed.

Ratan Tata personally intervened.

There’s an old story — barely remembered — that when the Tata Group had to decide whether to sell off Trent or double down, Ratan Tata asked just one question:

“Can this company build India’s next great retail format?”

When the answer came back “yes,” he didn’t just approve funding.

He gave strategic clarity — and protected it from being merged into Titan or Tanishq.

That single decision kept Trent alive.

But what’s wilder? What came next.

The Zara JV.

In 2010, when Trent and Inditex shook hands to launch Zara in India, almost everyone thought it was a PR stunt.

“Fast fashion in India? Not a chance.”

“Price point is too high.”

“No one in Tier 2 will buy it.”

Today? Zara India clocks ₹2,769 Cr in revenue and it’s among the most profitable fast-fashion formats in the country.

So yeah, Trent’s aura isn’t just built on numbers.

It’s built on a series of bold decisions — some from the boardroom, some from the floor.

And every time someone thought it was too small to matter, Trent proved otherwise.

But here’s the catch: markets don’t reward stories forever.

Eventually, they reward performance. And that brings us to the next chapter.

What Trent Taught Me

This isn’t the story of a multibagger.

It’s not even the story of a mistake.

It’s the story of a lesson that gets harder to learn the longer you stay in the markets.

Because the longer you’re here, the more you want to believe that you’ve seen this movie before.

That you can recognize the next Titan.

That you can ride the next 100-bagger.

That this time, it’s different.

And sometimes — for a while — it really does feel different.

Trent taught me that even the best businesses, the most operationally efficient, brand-rich, execution-led companies… can still become dangerous when bought at the wrong price.

It taught me that valuation risk is invisible when the story is glowing.

It also taught me that conviction becomes concentration without you realizing it.

That ₹2,000 buy doesn’t feel like a big deal.

But then you add more at ₹3,000… then ₹5,000… then ₹7,000.

And suddenly, the stock you loved has become 45% of your entire portfolio.

Not because you believed in the numbers.

But because you believed in the name.

Trent reminded me that loyalty is a beautiful thing — in families, in friendships, in principles.

But in markets? Loyalty without limits becomes exposure without exits.

And the toughest part?

Trent didn’t blow up.

It didn’t crash.

It didn’t miss numbers massively.

It didn’t issue a profit warning.

It just slowed.

And that… was enough.

Case Study Learnings — If You Only Remember One Thing

You don’t study a company like Trent to decide whether it’s “good” or “bad.”

You study it to understand the invisible shift — the moment where story, price, and performance quietly drift apart.

So here’s what I hope you take away from this case study:

1. Valuation always catches up.

Even if the business doesn’t fall, the multiple can — and will.

2. Narrative ≠ Earnings.

Great brand? Loved by youth? Scaling fast? Awesome.

Still doesn’t justify a 228x P/E.

3. Your biggest mistakes won’t be bad businesses.

They’ll be good businesses bought too high and held too long.

4. Loyalty is not a thesis.

“Because it’s Tata” is not an investing framework. It’s a belief system.

And belief systems don’t work well in quarterly earnings.

5. Conviction becomes concentration… quietly.

Nobody sets out to let one stock become 45% of their portfolio.

But momentum… is seductive.

6. PEG is your reality check.

It’s not perfect. But when PEG crosses 4–5… you need to stop and ask:

Am I paying for performance, or for comfort?

7. Don’t fall in love with what you can’t control.

You can love Zudio. You can wear Westside.

But that doesn’t mean the stock will love you back.

This case study wasn’t written to dunk on Trent.

It was written to remind us that even the best companies… come with baggage when valuations run too far ahead.

Trent is still a beautiful business.

But the question isn’t “Is it beautiful?”

The question is:

Is it still worth the price the market is asking you to pay for it today?

That’s for each investor to answer — based on their own goals, their own risk appetite, and their own humility.

Written by Shubham Borkar | Research & Insights by Shikshan Nivesh

[Educate · Analyze · Invest]

Disclaimer: This is an educational initiative by Shikshan Nivesh and does not constitute investment advice.

Sources & Disclosures

All financial data, store metrics, and operational insights referenced in this article were verified using the official investor presentations of Trent Ltd for Q1, Q2, Q3, and the unaudited Q4 FY25 business update (released April 5, 2025), as well as the FY24 Annual Report. The CARE Ratings credit report dated November 2024 was also used to cross-reference certain financial and segmental data. JV figures for Zara and Star Bazaar were included based on management commentary and publicly available disclosures.

All charts and financial calculations were independently prepared by the Shikshan Nivesh team based on publicly disclosed company filings. Chart data was subjected to a rigorous process of checking, re-checking, and cross-verification across multiple sources to maintain the highest possible standard of data integrity.

Please note: All Q4 FY25 and full-year FY25 figures referenced in this article are unaudited and subject to revision upon final statutory audit. PEG ratios, P/E multiples, and related valuation metrics have been manually calculated for educational purposes and are not intended as forward guidance.

By Shikshan Nivesh

For more insights, follow Shikshan Nivesh :

🔗Visit us on: Shikshan Nivesh

🔗 X : @ShikshanNivesh

🔗 LinkedIn: Shikshan Nivesh

🔗 threads: @shikshan_nivesh

👉 If you found this helpful, share it with someone who’s tracking India’s growth story or looking for simple, research-backed investing insights.

Leave a Review